Effective decision-making and the role of labour market information (LMI) in career guidance

Learning Objectives:

- To explore the relationship between effective career decision-making and LMI.

- To review selected frameworks that guide the use of LMI in effective decision making for careers.

[Reflective questions are included, to which there is no one clear answer, because they relate to complex issues that often result in divergent opinions amongst career practitioners.]

What are the issues?

Governments around the world are becoming increasingly aware that careers guidance practice underpinned by high quality, reliable and accurate LMI, helps individuals make effective career decisions. In the wake of the COVID pandemic, it is also being recognised that it can help achieve workforce re-balancing. As a consequence, there has been a proliferation of LMI systems in countries around the world designed to make access to high-quality LMI easier for those making career decisions, via websites and other mechanisms.

But the increased availability of high quality, reliable LMI, is simply not enough. Its effective integration into career guidance practice requires an understanding of the influences that shape the decision-making of clients/customers/learners. This understanding helps career practitioners structure the LMI they make available to their clients/customers/learners in a way that reflects the nature of decision-making processes in different contexts (OECD, 2020).

Early frameworks that were developed to help us understand the decision-making processes for career choices tended to assume that individuals adopt a rational approach to career decision-making, that maximises benefits to them (defined, for example, as pay, working conditions, prospects for promotion, etc.). These early approaches still dominate career practice today. In this approach, high-quality LMI is central, since it provides the basis for rational career decision making. For example, to maximise financial rewards, it is necessary for individuals to have access to LMI that gives a comparison for of pay-rates across occupational sectors.

Reflective question:

Just how rational are you?

Try to think about a decision you have made when you had the information that enabled you to weigh up all the proc and cons of that decision.

Now try to think about a decision you made when you didn’t have the necessary information, so (in retrospect) probably did not make the best decision you could.

How rational do you think your clients/customers/learners are when they make career decisions? Practitioners can usually think of examples when clients/customers/learners ignored the information they gave them (for example, deadlines for submission of application forms or jobs).

In reality and because of the complexity of the decisions needed for educational/training pathways and careers, individuals are likely to use a range approaches when confronted with these choices, instead of sticking to a purely rational approach.

Competing perspectives – no right approach?

‘Evidence shows that access to information alone is not sufficient for effective support’ (OECD, 2020, p.7)

Understanding the nature of the career decision-making process and how LMI can be integrated into these processes will help providers of career guidance support services to increase their effectiveness. Much has been written about career decision making and those who have researched the process over many decades describe it in very different ways. It is important to recognise that no one of these frameworks has been proven to be stronger, or more robust, than others.

One approach that has attracted much attention recently comes from the discipline of behavioural economics. This argues that the way(s) in which an individual evaluates different tasks changes over time and across different social contexts. The insights provided by behavioural economics can usefully be combined with those from new, specialist theories of career decision-making, together with the tried and tested theories upon which much careers practice is currently based.

This learning unit presents selected summaries of different theoretical contributions for you to consider that provide contrasting frameworks for using LMI differently during the career intervention process.

It then reviews the differences in the ways some of these contributions argue that LMI should be integrated in career decision-making.

Perspectives on career decision making

Psychological

Many psychological approaches to career decision-making have at their core the assumption that individuals have control over their destinies and are able to exercise free choice and autonomy. One such example proposes that career decision making is essentially a rational, three-stage process. That is, individuals:

- will gather relevant information (based on reliable LMI); and then

- weigh up the costs and benefits of different job options, in relation to their own abilities and circumstances;

- search for suitable job vacancies, being careful to making a decision that optimizes benefits to themselves.

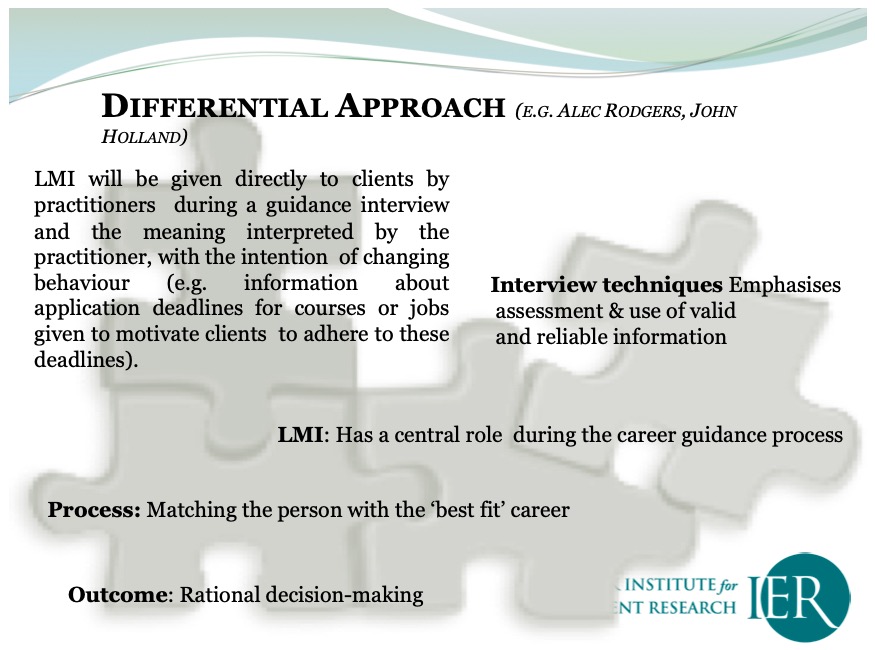

This approach, from differential psychology, has had a profound influence on career guidance practice since it appeared in 1908 (Parsons, 1908) and despite growing criticisms, continues to exert influence on career guidance practice.

Other influential psychological theories include those with roots in: developmental, humanistic, psychodynamic and social learning approaches.

Sociological

A second approach is derived from the discipline of sociology and places importance on the contextual, systemic, or structural constraints with which individuals have to grapple in their career journeys and over which they may feel they have little, or no, control (Bimrose, 2019). It focuses on the statuses ascribed to individuals at birth, such as gender, racial and ethnic group, or socio-economic (family) background, which have an undeniable impact on life chances, including career progression. Because these are (generally) fixed, then a priority for effective career practice is to work with individuals to accommodate and/or navigate contextual constraints, accepting that some are much more constrained in the career choices they make than others. Often referred to as ‘deterministic’ or occupation allocation, this approach aligns closely with behavioural economics in many respects.

A summary of the main approaches to career decision making:

Reflective questions:

Looking back on your own career to-date, which of these frameworks explain best why you made the career decisions you did, at the times you made them?

When you think about your clients/customers/learners, which of these approaches seem to make most sense?

The role of LMI

Irrespective of which of these broad approaches you feel is most robust, each gives a clear steer about the role of LMI in career decision-making. They highlight how the integration of LMI into career guidance practice requires a deep understanding of the decision-making process of client/customer/learner and that LMI needs to be structured to reflect the nature of the decision-making process. For example:

The differential, or matching approach – LMI is central to career decision-making, which is essentially a rational process.

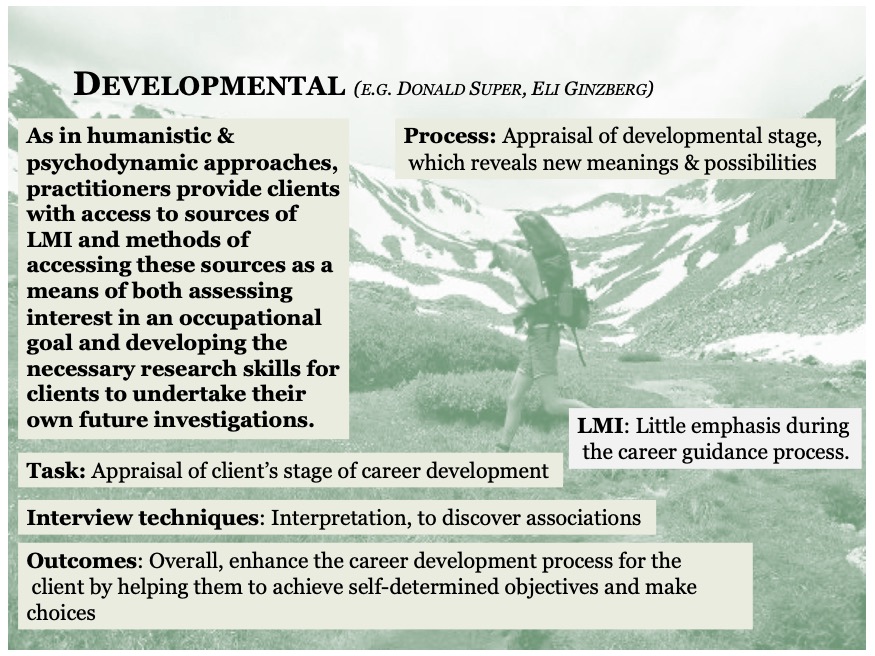

This compares with a developmental approach, where the practitioner makes sure their clients have access to high quality LMI, but not necessarily during interviews or group work.

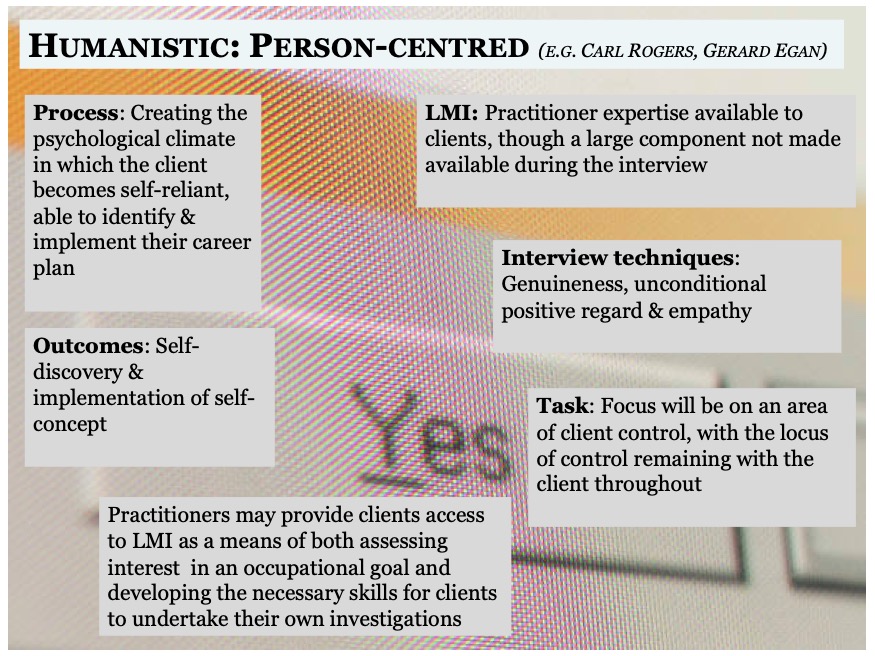

Both these approaches contrast with a human-centred approach, which allows the client /customer/learner to determine how, when and what LMI is accessed and used.

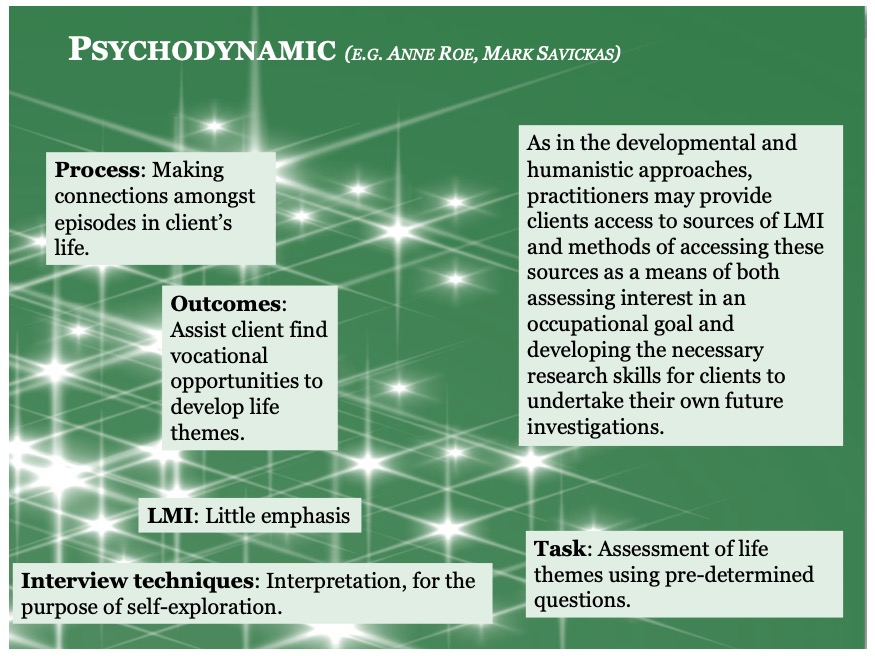

Similar to developmental and humanistic approaches, here there is little direct emphasis on LMI during career interventions. More concern is focused on developing the research skills of clients/customers/learners, so that they will be able to help themselves in the future.

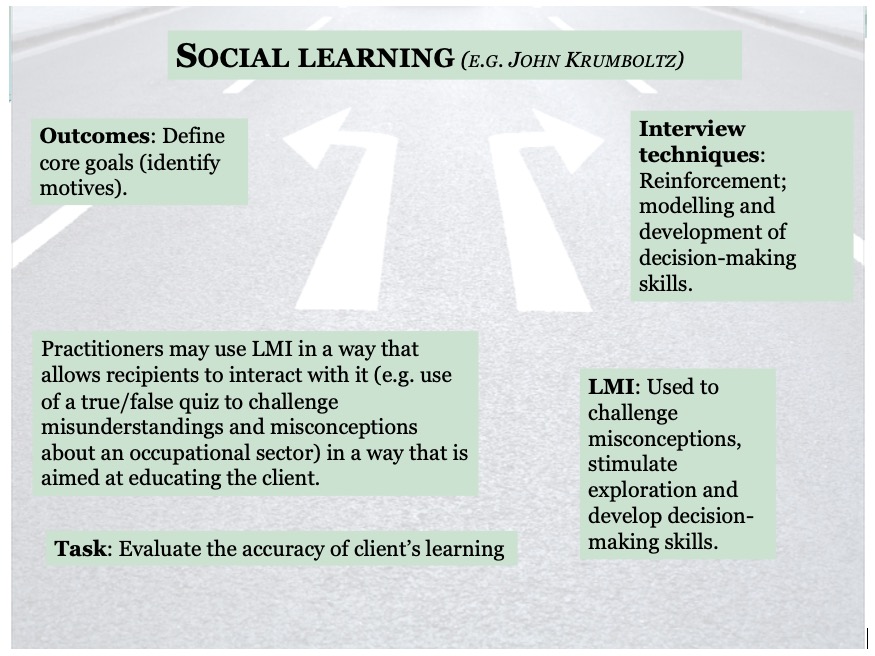

In the social learning approach, the practitioner fosters more of a teacher/learner relationship, so uses LMI to challenge misconceptions, reinforce ideas, for modelling, etc., focusing on the client’s learning – constantly assessing how accurate is it, what is missing, etc.

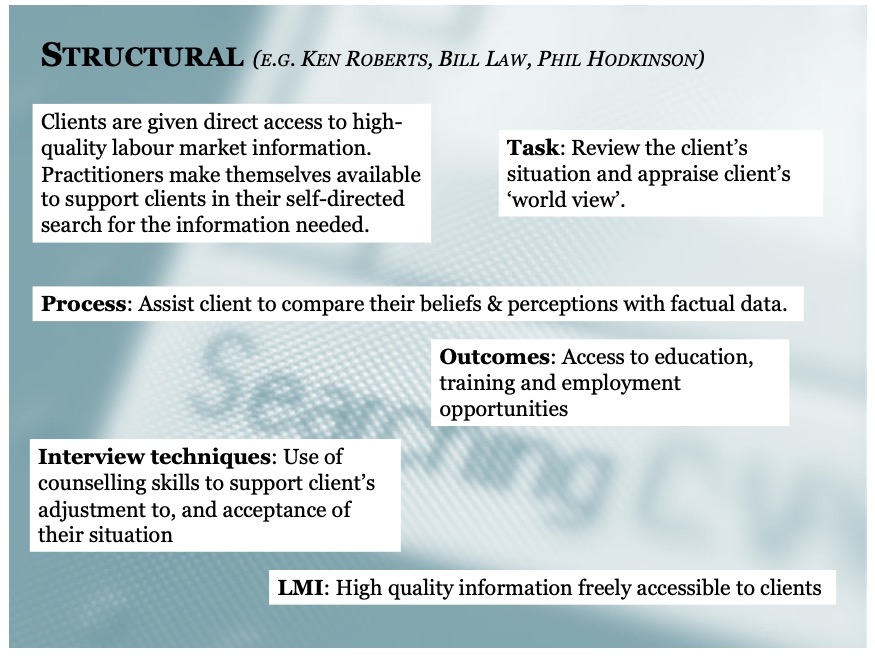

Derived from sociology, with the main focus on the client’s situation and circumstances – what constrains and what enables career progression – the structural approach foregrounds social equity issues.

Eclectic

A third category of approaches can be typified as eclectic, combining elements of these two broad categories with others. Such approaches foreground the combination of factors like: what is known to be available; what is perceived as possible; and what is regarded as desirable.

For example, the Systems Theory Framework of Career Development (McMahon & Patton,2006).

Behavioural economics

Behavioural economics models provide insights into how individuals’ valuation of tasks changes over time and how people may make different decisions in different social contexts (Hofer, Zhivkovikj, & Smyth, 202026; Hume & Heal, 201627; Taylor, 2016a, 2016b). This understanding needs to be linked to insights from existing frameworks and new, specialist theories of career decision-making (Alexander, McCabe, & De Backer, 2020).

This approach argues that many individuals suffer from ‘choice overload’ when faced with complex decisions, so tend to postpone decisions or opt for a default option (following the advice of friends, peers, parents or other influencers).

The framing of options greatly influences the decision-making process, meaning how the decision problem is framed (Alexander, McCabe, & De Backer, 2020).

Factors that make a real difference include:

- The role of parents/carers

- The role of schools

- Access to information

- Financial literacy

- The perceived value of education

- Avoiding gendered stereotypes

- The importance of role models.

- Timing of careers guidance

- Idea-forming events

- Hard choice moments

- Feedback points (CG)

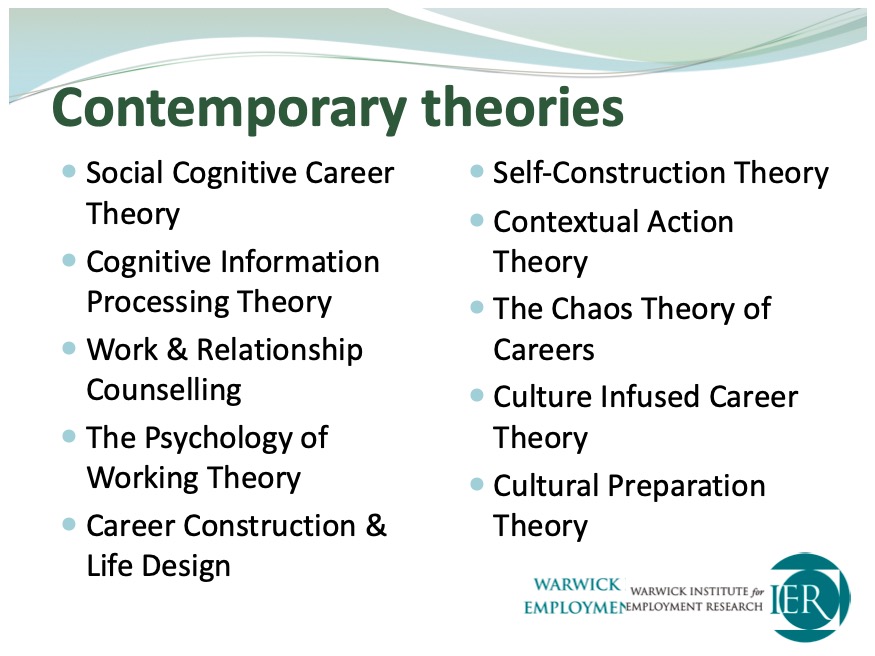

New theoretical insights

In addition to these broad theoretical positions are contemporary theories of career decision making.

(Arthur, N. & McMahon, M. (eds). Contemporary theories of career development. International Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group)

Conclusion

Overall, the process of career decision-making, throughout an individual’s lifetime, is an ongoing process that is not necessarily linear. Regarding it as a continuum, rather than a one-off process, is probably more accurate for most individuals. The social context in which these decisions are formulated and implemented are crucially important.

‘Effective career guidance is timely, motivating and targeted to the needs of individual learners.’ (Alexander, McCabe, & De Backer, 2020, p.41).

‘To improve career decision-making, governments need to provide support for decision-making – through guidance, in schools and post-secondary education, and through the provision of robust information. But the provision of information needs to be structured to reflet the nature of the decision-making process. This means that information, idelly, should be personalised, trustworthy, meaningful to the decision-maker and provided as needed (but no more)’. (Alexander, McCabe, & De Backer, 2020, p. 44).

Previous ‘LMI for All’ learning units available from the LMI for All website have explored other crucial questions related to LMI in practice, such as:

What is LMI and why is it important?

Choosing amongst sources of LMI

LMI in career guidance: biased or impartial

References:

Alexander, R., McCabe, G. and De Backer, M. (2019). Careers and labour market information: An international review of the evidence. Reading: Education Development Trust.

Barnes, S-A., Bimrose, J., Brown, A., Gough, J. & Wright, S. (2020). The role of parents and carers in providing careers guidance and how they can be better supported: International evidence report. Coventry: University of Warwick.

Bimrose, J. (2019). Choice or constraint? Sociological theory. In Arthur, N. & McMahon, M. (eds). Contemporary theories of career development. International Perspectives. London and New York: Routledge: Taylor & Francis Group. pp 166 – 179.

Gatsby (2014). Good Career Guidance. London: The Gatsby Foundation.

Hofer, A.R., Zhivkovikj, A., & Smyth, R. (2020). The role of labour market information in guiding educational and occupational choices. OECD Education Working Paper No. 229. Paris: OECD.

Hume, S., & Heal, J. (2016). Moments of Choice. London: The Behavioural Insights Team.

Institute for Employment Research & Enterprising Careers (2006). Labour market information for career decision-making. A report to Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Available from: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/ier/publications/2006/0402lmidecisionmakingpdf1.pdf

McMahon, M & Patton, W. (2006). The Systems Theory Framework of Career Development and Counseling: Connecting Theory and Practice. In: International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. Vol. 28, p 153-166.

Taylor, R. (2016a). Moments of choice: How education outcomes data can support better informed career decisions. London: The Careers and Enterprise Company.

Taylor, R. (2016b). A response to the Moments of Choice research: A programme to support informed choice. London: The Careers and Enterprise Company.

Walsh, B. W. (1990). A Summary and Integration of Career Counseling Approaches. In Walsh, W. B. & Osipow, H. (1990) Career Counseling: Contemporary Topics in Vocational Psychology, Hove & London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.